The Gist

- Language drives mindset. Calling people “users” creates emotional distance and subtly shapes cold, mechanical design choices.

- Human-first labels matter. Switching to specific roles—customers, members, guests, citizens—reframes intent and boosts empathy.

- Rituals reinforce culture. Practices like Amazon’s empty chair and IKEA’s store walks keep real people at the center of decisions.

- AI raises the stakes. As agents become “users,” precise, human-centered language is crucial to avoid dehumanizing experiences.

Picture this. You walk into a fancy hotel lobby with your suitcase, eager to check in. A smiling employee greets you with a big smile and says, “Welcome, dear user!”. Sounds weird, doesn’t it?

Yet, in the digital space, “user” has been our default label for the very people we are trying to delight. We don’t talk about guests, clients, members, citizens, etc., we speak about our users. And, like all labels, it carries baggage.

Table of Contents

- When Marketing Borrowed 'User' From Tech

- The Problem With Ubiquity

- Words Shape Culture

- Designing For People, Not Users

- Moving Beyond User

When Marketing Borrowed 'User' From Tech

From Adjacent to Married

My background is deeply rooted in technology, but for most of my career, I have worked at the intersection of technology and marketing, exploring how tech can provide better digital experiences, spark engagement, increase conversion and strengthen brands. This is what I’ve been doing in marketing.

Twenty-five years ago, marketing and technology were not even adjacent. They spoke different languages, had different KPIs and carried fundamentally different mindsets. That intersection is today a marriage, since digital is a fundamental aspect of marketing. Yet, there was a curious overlap: marketing started to use the term “user” borrowing it from tech, and somehow it stuck.

Users Versus End Users

Funny enough, when I started setting up systems for marketing, I ended up having “users” (the marketers) and “end users.”

I always felt the term “user” a bit off, but it was not until a recent conversation that I became more cognizant of the term user. In this conversation, a colleague said to the group, “Please, don’t call them users. Do you know which other industry labels people that way? Yes, drugs.” That landed hard. Suddenly, the term bothered me more. Sounded cold and mechanical.

A Brief History Of 'User'

The term “user” was popularized as computers emerged in the mid-20th century. People who programmed were “programmers,” and those who used computers were “users.” Back then, no one could have anticipated that within a few decades, nearly everyone would become a computer.

Related Article: Beyond the Mirage: A Data-Driven Blueprint to Tame Martech Complexity

The Problem With Ubiquity

When Every Journey Becomes A 'User' Journey

Now, take a look at how the word runs. We discuss user experience, user interface, user stories, usernames, user roles, user personas, user research, user acquisition, user churn, user journeys, user engagement or user-generated content.

Imagine the 'Operator Experience'

It’s everywhere! Now let’s swap with its original equivalent. At the dawn of computers, people who used them would also be called “operators." Users and operators were used interchangeably. What would you think if someone talked to you about “operator experience” or “operator interface”? Yes, absurd. Calling them “users” is not less ridiculous, but is just normalized by repetition.

Words Shape Culture

Cast Members, Associates and 'Ladies and Gentlemen'

This matters because words matter. Labels matter. Many companies understand it well. Disney doesn’t call its staff “employees," it calls them “cast members.” In the same fashion, Walmart has “associates,” Apple has “geniuses,” Google has “Googlers,” and The Ritz-Carlton has “Ladies and Gentlemen serving Ladies and Gentlemen.” These words shape how people feel about their role, and how companies design experiences around them.

Now, look at the other side. Hotels welcome guests, and Airlines board passengers. Gyms sign up members. Universities enroll students. Retail serves shoppers. Governments serve citizens. No one approaches their customers by saying “hello, dear user.” They know better. We understand that a label changes the relationship.

Some organizations go further. Jeff Bezos was known for leaving an empty chair in meetings to represent customers. IKEA continually sends leaders to walk the store as customers. These are not small gestures; they are powerful reminders that people, not users, are at the center.

Designing For People, Not Users

Human Language Builds Empathy

Organizations invest heavily in humanizing their brands and becoming customer-centric at multiple levels. And they’re right to do so, because it makes their brand stronger, impacting revenue and profit positively. But when the very foundation of the ecosystem is built on “users,” something feels off. We all agree “user” isn’t the most human-centric term. Language shapes how we see the world. Subtle changes foster empathy. Just as showing patient photos increases empathy in radiologists, humanizing our language helps us design for the people we want to please and serve.

The timing for having this conversation couldn’t be better. AI has the potential to evolve into the most impersonal technology that we have encountered or the most human-centric. At the same time, AI is stretching the concept of users, as agents are increasingly turning into “users” (and customers). As AI becomes increasingly embedded in everyday life, clinging to the term 'user' risks creating distance when closeness matters most. If we keep designing for users, we risk losing sight of the human altogether.

Moving Beyond User

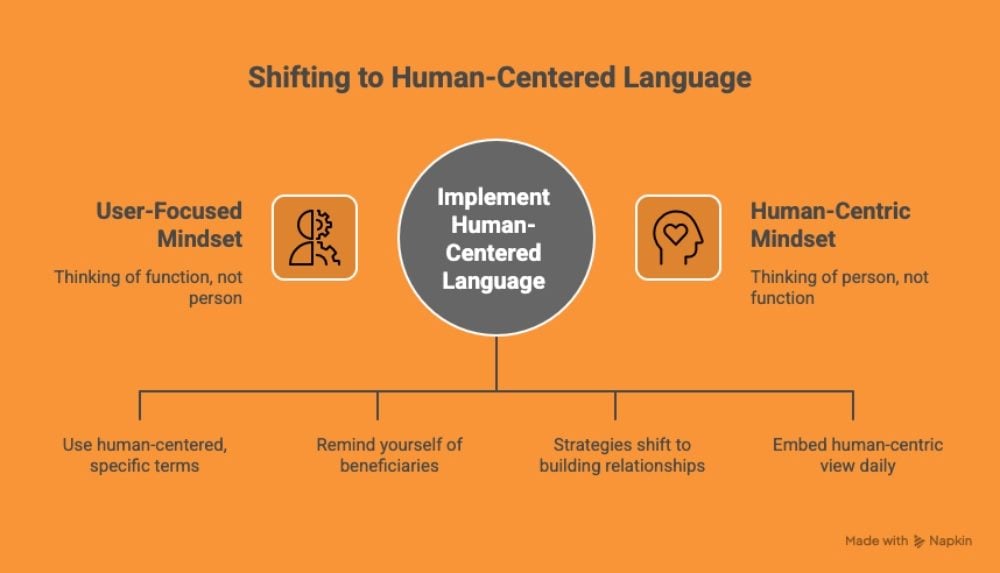

So, what do we do about it? It’s not about swapping one word for a different one. It's about shifting perspective. It’s about thinking about the person, not the function. Here are some ideas to start.

Use Specific, Human-Centered Language

Borrowing a concept from the tech world, Ubiquitous Language, by Eric Evans, we could strive to be as specific as possible, and strive for a human-centered language. Instead of a user profile, let’s talk about a member profile, a user story, a shopper story, an editor's journey, etc.

Change Your Internal Rituals

As Bezos did, try to put in your routine meetings aspects that continuously remind you what you are working for, who the beneficiaries of your system, your campaign, or your app are.

Let the New Language Inform Your Process

When you start talking about customer attraction instead of user acquisition, your internal strategies might start changing. On a more transversal and interdisciplinary way, people will be thinking about building relationships and value, not just about keeping an active user on your platform. Get creative, instead of user acquisition, talk about community growth, or instead of user retention, about customer loyalty, or instead of user persona, simply persona.

Be Intentional About The Change

This type of change won’t happen overnight. As we have seen, “user” is deeply ingrained in our vocabulary, our measurements and our mindsets. But being deliberate about the shift can embed a more human-centric view into the very fabric of an organization—making it not just a principle but a daily practice.

Finally, this is not about just semantics. It’s about reshaping the way we think when we are building. Labels help shape intent. Call them a user, and you’ll think of them as someone who clicks buttons; call them a customer, and you’ll think of them as someone you serve.

Language helps set the tone for design, strategy and culture. The next time you’re about to write “user,” pause. Ask: Who is this really for? A customer? A client? A guest? A citizen? A patient? A participant? A creator?

Learn how you can join our contributor community.